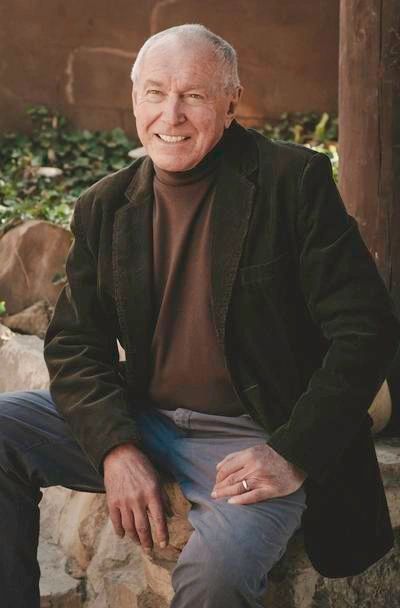

ABOUT STEVE

2019-2020 READER VIEWS LITERARY AWARD WINNER

2020 BOOK EXCELLENCE AWARD FINALIST

Talk about far-fetched, Steve Bassett, in getting from back there to here, meandered along a circuitous path that hardly resembles your usual stodgy curriculum vitae.

There were hurdles, of course, everyone has them, that included childhood escape from the mean streets of Newark’s notorious Third Ward. His mother died of misdiagnosed spinal meningitis when he was seven. Then followed five years of orphanage time at two Catholic institutions. After the good Sisters of St. Joseph provided a high school college prep education, it was off to the Army for two years.

Peacetime Korea was an eye opener. A posting with the 7th Infantry Division along the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) provided binocular assisted eyeball-to-eyeball contact with the Commies and, of course, the North Koreans were staring right back.

Memoirists like to point to that bright flash of epiphany that can really muddle things up. Preconceptions and rock solid certainties can take a beating. The eye-opener for Steve occurred in the most unlikely of places, Aberdeen, South Dakota. He was one of the Army veterans returning home aboard a passenger converted C-46 cargo plane that almost crash landed during a refueling stop. The plane descended too early, bounced along the runway threshold, and almost flipped before the pilot regained control and got the ship airborne again.

While the plane circled to gain altitude for a new approach, car headlights closed in on the small airport from every direction. When the old C-46 taxied to a stop at the terminal, it was greeted by about fifty men, women and children, some still in pajamas and from the looks on their faces, very disappointed. A young Puerto Rican GI shared Steve’s bewilderment after he scanned the all white crowd and confided, “Jesus Christ, just look at them. They all came out here to see a crash, got out of bed for it and now they’re going home disappointed.”

For the inner city escapee from New Jersey, the incident was indelible. The South Dakota voyeurs were homogenous strangers, aliens to a guy who had shared the sidewalks of Newark with blacks, Latinos, and every ethnic shade of white. At that moment the embryo of what was to be a 35 year journalism career began to form. It was shaped by the realization that he really didn’t know a hell of a lot about the country and he wasn’t going to learn very much as an obit writer or a third-string night police reporter on a big city sheet.

A reporter had to get to the core values, found along every Main Street and undoubtedly shared by the thwarted thrill seekers in Aberdeen, before he could get a handle on anything. Was it an illusory quest? Perhaps but it is still an enticing brass ring whose promise for this reporter and author has always been worthy of pursuit.

Another hurdle awaited Steve when he made the transition from straight news and documentary film production to author. He was stricken with premature macular degeneration losing the central vision of his left eye and a portion of his sight in his right eye. As was the case with his mother, his condition had been misdiagnosed. Doctors said he was too young, took a wait and see attitude and then it was too late. Steve had committed himself to serious writing and this setback was turned into a strength.

During three of the five years it took to complete “Golden Ghetto,” he was legally blind. This was also the case during the three years it took to complete “Father Divine’s Bike,” the first of a proposed “The Passaic River Trilogy.” Ambitious? Damn right it is, and hopefully an inspiration to thousands of the sight impaired who dream of a life of writing. His enduring gratitude goes out to the dedicated therapists at the Veterans Administration Tucson facility for sight impaired veterans.

Patience was the keynote. New living skills had to be learned and in Steve’s case, mastering of voice activated computer programs without which none of this would have been possible.

---

REVIEWS FOR LOVE IN THE SHADOWS

- Love in the Shadows is filled with love, betrayal, past traumas, forgotten secrets, hidden agendas, ulterior motives and acceptance. Journey of different women who have been a victim of domestic abuse and a man with his concealed identity teams up and gives birth to a fantastic story of retaliation.

- Beautiful scenic views, amazingly developed plots, and a well-painted picture—all are the words that best describe the book. Steve Bassett has successfully managed to confine an engaging story with all the necessary elements that will keep the reader on the edge of their seats—a captivating read.

- The writing is gorgeous, and the drama builds up on every page, thanks to the author’s excellent dialogue and gift for humor. – Reader’s Favorite, 5-Star review

- Love In the Shadows is a gripping tale of power, corruption, and the quest for justice and revenge…. an excellent read for fans of historical fiction. – Reader’s Favorite, 5-Star review

- Readers will be guided through the smokey dark back rooms of bars and taverns, the bright lights of society, and the sleazy halls and offices of a metropolitan judicial system… And if you are a fan of old black-and-white detective gangster films of the 1940s you need to add Steve Bassett’s “Love in the Shadows” to your reading list. - Reader Views, 4-star review